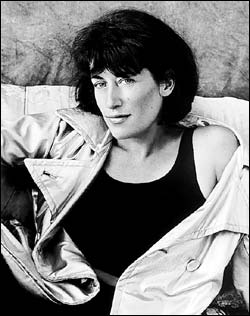

Kate Sekules The Boxer’s Heart: How I Fell in Love With the Ring;

Lynn Snowden Picket Looking for a Fight

by Ann Marlowe

December 20 – 26, 2000

“Both boxing and drugs are ways of avoiding pain,” punk rocker-turned-journalist Kate Sekules writes in her first book, The Boxer’s Heart. “This pain means I don’t feel that pain. . . . Feeling lonely and pathetic and static and pessimistic—that is pain. Getting hit is nothing.”

Sekules here follows Freud, who wrote in Beyond the Pleasure Principle that soldiers who were wounded were less likely to develop the psychological symptoms of shell shock. A real physical injury fixes the terror to a circumscribed event that can be worked through and gotten over. Though she doesn’t quite realize it, her insight also might explain why neither she nor Lynn Snowden Picket, who wrote Looking for a Fight, stuck with boxing competitively. Middle-class professional writers weathering bad spots with men, they weren’t wounded enough psychologically to need a lifetime of bruises.

Sekules is an unlikely pugilist: an English-born travel editor at Food & Wine who has a Fitness Instruction Certificate from NYU. She spent years worrying about her size (apparently she is muscular, big-boned, over five-foot-eight) and her weight (she fought at a tenuously maintained 147), and boxing finally freed her from this preoccupation with her appearance. By the end of her memoir, she has quit fighting professionally, but still trains at Gleason’s Gym, where, she tells us, 14 percent of the membership is now female.

Picket is vaguer about her background, though she mentions a dad in the military and some painful playground bullying. Her exposure to boxing doesn’t appear to have made her happier or freer. Swamped by psychosomatic symptoms, Picket quits her trainer, Hector, with no notice after her first public (amateur) bout. Although she calls him a bully after the fact, I wonder how Hector felt about the time and energy he had invested. What strikes an especially sour note is that Picket tells us that she “makes a living as a participatory journalist,” becoming a stripper to write about a strip club and spending three whole days and nights (whew!) on an aircraft carrier—”all in the name of a story.” (Her first book, Nine Lives, is apparently an account of a year spent at these and other jobs.) But she tells Hector that she is serious about learning to fight.

Perhaps the participatory-journalism angle explains why Picket’s vaunting of her athleticism rings false. We learn that she can do a “set” (her word) of three pull-ups, the exercise she terms “my litmus test for manhood,” and boasts of doing 10 “nearly perfect” push-ups. By the book’s conclusion, Picket views her boxing experience as “a horrible nightmare,” and in a final chapter explaining the health hazards of boxing from blows to the head, Picket concludes, “If I had known then what I know now, I would have never gotten into a ring.” Picket also seems to consider boxing the only form of fighting. Neither she nor Sekules thought of trying one of the many martial arts that don’t allow punches to the head in tournaments.

To what extent were these women really serious about boxing, as opposed to writing about it? Sekules is more convincingly devoted than Picket—she trains daily, her athletic past includes international amateur competition in softball, and she fights two professional bouts, described with piercing accuracy. (“An opponent will nail you, stalk you around the small enclosure, take advantage of every weakness; no compassion. There are no more gender privileges.”) But my antennae went up when I read that she worked the phones “in a high-class Manhattan brothel, a job I took because I thought it would be interesting to get to know the girls.” Another participatory journalist? Sekules turns down numerous fight debuts and moves to England when the time draws nigh. And at the end, like Picket, she blames her trainer that things didn’t work out: “He hadn’t trained me right. He should have made me spar harder.”

Reading these memoirs, accented with whining and excuses and blame tossing, it is tempting to try to imagine how we would react if they were written by men. However anxious each author claims to be to break down the barriers to female equality in sports and society, neither is willing to shoulder some of the historic burdens of masculinity, like stoic endurance of physical pain and acceptance of responsibility.

Both writers take it for granted that male trainers would be attracted to them, but neither looks at what she hopes to get from this intense relationship. Neither woman analyzes her own transference onto her (male) trainer, but one wonders, given the boyfriend problems Sekules details and the divorce that prompted Picket to try boxing.

Sekules is less of a complainer, but she seems trapped by the same rigid gender roles she says she wants to overthrow. She is horrified when her boyfriend becomes progressively more turned on by her growing strength. Seems there’s no pleasing her: “To adopt willingly the dominant position is one thing, but to be placed there against one’s will is abuse.” Isn’t she placing her boyfriend in a dominant role just because he’s male? In a society without gender constraints, wouldn’t men be free to choose to be dominated?

Both writers are full of these unanalyzed contradictions. They demand unconditional love and resent even the simple requirement that they show up consistently and take their training seriously. They expect their inner fervor to make up for their lack of commitment; they want to be given special privileges because they’re girls. In the end, Sekules’s and Picket’s memoirs are as interesting for what they don’t address as what they do.